Traditional structures were designed to allow moisture to evaporate where modern construction relies on systems of barriers preventing moisture from penetrating the structure and building materials.

Increased moisture within a wall whether old or modern, will drastically increase the likelihood of decay. Exterior paint is designed to prevent water penetration, but this also prevents evaporation. Strong cement renders have similar effects except they are more susceptible to cracking and breakdown resulting in a more dramatic decay and water infiltration. Old walls were usually “pointed” which, was a cement rich mortar. Water was still able to evaporate back through the mortar which, forces it back out, exiting through the mortar face. This can lead to an increase in decay due to salt deposits left behind and the mechanical action of frost and water freezing within the wall. Pointing is best done with a soft lime mortar with lower strength to the masonry. Mortar does and will decay but is much cheaper and easier to re-point at intervals than replacing bricks or stone blocks.

The misconception regarding breathing is that old structures, homes and large estates did breathe because the walls were masonry, not 2 x 4s and sheetrock. The “breathe” concept came from old and historic structures, villas, and the like. These were constructed of thick walls and had means to absorb moisture, stop it, then the wall paint and mortars and other masonry materials would draw the moisture back out and release it by drying. Lime mortar was used internally because it allowed moisture to evaporate from within the thick wall. Externally, lime was also used for the same purpose as a wash or lime base paint. If the exterior face is sealed on a building, preventing water evaporation, then the internal surface will end up damp and cause a cooling effect and tremendous heat loss. Older buildings will function perfectly if allowed to work as originally intended. Mortars, plasters, renders and finishes would all be permeable. All lime based mortars, renders and lime-wash finishes were applied to allow for the breathing of moisture.

Returning to old homes and insulation; it is complicated and not a one-size-fits-all solution, particularly since old homes before the mid-1900s, were constructed without insulation.

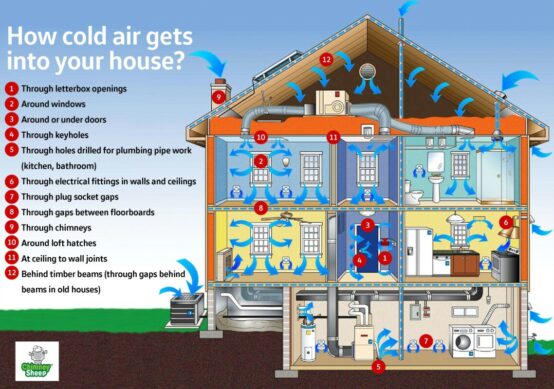

Water is and was the greatest enemy, so builders designed in a manner allowing water to not only get into the walls in minute amounts but, thanks to the loose envelope, the structure would dry out quickly. A couple of decades later, we have wall cavities stuffed full of fiberglass which, acts like a sponge when wet. Adding insulation where it was never designed to reside, causes a myriad of moisture problems with concurrent moisture related issues. A house can never be too tight however, a tight building envelope can have issues, and this is due to air sealing. Houses need to dry out thus, a structure must be thought of in systems such as, indoor air quality, back drafting combustion, high humidity, and mold.

For old homes, the rule of thumb is again, attic, basement and or crawlspace. Always begin in the attic, always! Depending on the type of roof, if for example wood shingle which, gets wet then properly dry or, if the roof was replaced with adequate waterproofing, underlayment and flashing, then insulating the underside of the roof in the attic is an option for an old home. Otherwise, stay away from the underside and do the attic floor/ceiling and seal all air leak gaps. Leave the walls alone. The walls in old homes are very complicated and expensive to do properly, such as, completely dismantling the walls, the siding etc. Move to the basement and or crawlspace. There is plenty to seal and caulk in those areas, that coupled with a good mineral wool which, is critter inhospitable vs fiberglass, you will be able to increase the warmth in the home significantly. Sealing means, baseboards, window trim, weather stripping, add storm windows and thick drapes.

Draught proofing is crucial and should be done prior to insulating an old home. For old historic homes, those three areas previously mentioned to insulate are the easiest to do producing the most effective results. There will also be less historic value that might prevent the required retrofit permits. These three areas are where radiant barrier can be used to increase the heat retention in the living quarters.

Energy used for space heating is 42% vs cooling at 6%. Clearly, cooling a home costs much less than to heat. In older homes, old concrete brick filled heaters were great for large old very spread out homes because the heated blocks would slowly release heat during the day. Constant, gentle low temperature heating would heat the whole building. If made of thick walls (mass again) they would hold a lot of heat staying warm for days. Thermal mass was one of the concepts behind fireplaces with big wide chimneys constructed with lots and lots of bricks. The core of the chimney heated up and stayed warm releasing the heat to the home. Also, thick, dry walls mean warm during the winter; dry being the key.

To reiterate a previous article, Cold Climate Insulation, these three areas are where Radiant Barrier can be added to help maintain radiant heat in the areas it needs to stay. The basement ceiling, the crawlspace and attic floor (ceiling of lower floor) and air-leak sealing will bring an old drafty and cold home up to warm and comfortable.